Clear Challenges, Options

Several opportunities and challenges have emerged for the artisanal fi sheries sector in Sierra Leone following the adoption of the Local Government Act, 2004

03 / 2010

Between 1999 and 2001, Sierra Leone experienced a bitter civil war that culminated in a collapsed State. The domestic effects of the collapse were severe, with the total disintegration of public authority leading to increased mortality rates, massive flows of refugees and internally displaced people, capital flight, the loss of social capital, and repressed economic growth. Moreover, as research suggests, a country reaching the end of a civil war typically faces around a 44 per cent risk of returning to conflict within five years; there is thus an urgent need to both guarantee the physical protection of Sierra Leoneans and to create the conditions for an improvement in living standards so as to prevent the re-emergence of conflict.

As one factor deemed to have precipitated the conflict was the overcentralization of the State machinery following the dissolution of local councils in 1972, administrative decentralization was seen as a prerequisite for enhancing personal security and social welfare. The institutional basis for this strategy was the Local Government Act, 2004 (LGA2004), which specifies a list of functions/activities which were to be devolved by line ministries and agencies to local councils by 2008. Among those affected was the Ministry of Fisheries and Marine Resources (MFMR), which was mandated to transfer the management of artisanal fisheries to local government (in the form of the elected councils) under Section 56, subsection b (“Local councils shall issue a licence to anyone in a locality who owns a canoe”) and Section 57, subsection c (“Local councils shall charge fees for the extraction of fish and establishment of inland fish ponds”) of the LGA2004.

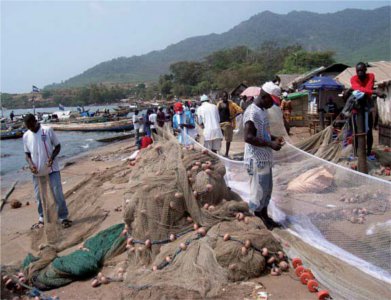

In natural-resource terms, this shift in managerial responsibility could have potentially profound implications as artisanal fisheries account for over 80 per cent of the national catch, with the sector supplying 67.9 per cent of primary commodity exports, accounting for 63 per cent of the country’s average daily animal protein consumption, and contributing to about 10 per cent of gross domestic product. Yet, while the decentralization of fisheries resource governance will have a critical role to play in enhancing participation and incorporating local knowledge on the characteristics of the fisheries resource, local capacity to assume these responsibilities is at present severely limited.

Accountability

Scholars have argued that devolution of functions is necessary for effective participation and accountability of the communities and user groups in resource management. In natural resource management, local institutions are better positioned than centralized ones to undertake particular functions such as conflict resolution and service provision. However, decentralization is not straightforward, and research has shown that the potential benefits of embracing local participation in resource governance can be undermined by a lack of transparency in implementing the reform; an inflexibility in incorporating local knowledge; the unwillingness of central government to hand back productive natural resources to local communities, and a failure to provide sufficient funding for the decentralized authorities.

Moreover, decentralization runs the risk of creating more local conflicts and social tensions, particularly if specific ecosystems fall within multiple political/administrative jurisdictions and/or non-representative local groups or if autocratic customary authorities are able to capture the benefits decentralization brings. These concerns are very much evident in Sierra Leone as the local councils established after the LGA2004 have assumed control over all artisanal vessels—despite initial concerns expressed by the MFMR over the limited participation of local communities, the lack of institutional capacity, the scarcity of localized management information, and the dearth of human/physical capital to undertake the necessary managerial and administrative duties.

There are six coastal district councils that have jurisdiction over the marine waters of Sierra Leone and, under the terms of the LGA2004, each is mandated to establish a Fisheries and Marine Committee. This comprises a chairman (who is an elected councillor), other councillors from within the council, representatives from fishers’ organizations and fisher communities, community elders and staff representatives co-opted from the MFMR. However, at the time of writing, of the six councils, only Port Loko had been allocated trained fisheries personnel to assist in the management of the resource. Moreover, while all six districts already possessed fisheries outstations—set up by the MFMR prior to the devolution process—that are responsible for data and licence fee collection, and training communities on fisheries management and resource sustainability, research suggests that the new institutional environment has allowed (in some instances) local politicians to subvert the effective operation of these facilities by appointing station managers who have never had training in fisheries management.

While it is clear that the MFMR currently lacks both the human resource capacity and funding to provide opportune support to the local councils, the councils themselves are further hampered by the pithy sums allocated to them by the central government in the start-up phase. Currently, each council receives the sum of 4 mn Leones (equivalent to just US$1,000) to run the affairs of an entire coastal district. Although, in the longer term, councils will, or should, become more self-sustaining once robust mechanisms have been put in place to collect licence fees and other duties payable, the current lack of funds severely impedes effective local revenue-collecting procedures.

DelPHE

The British Council Development Partnership in Higher Education (DelPHE) Programme—a collaboration among the Institute of Marine Biology and Oceanography (IMBO), Fourah Bay College, University of Sierra Leone, the Centre for the Economics and Management of Aquatic Resources (CEMARE), University of Portsmouth, United Kingdom, and the Centre for Maritime Research (MARE)/AMIDST, University of Amsterdam, the Netherlands—seeks to help local fi sher communities resolve challenges while promoting gender equity in the artisanal fi sheries sector in Sierra Leone. The project’s immediate impact has been its ability to engage the key resource stakeholders in an interactive manner to identify the strengths, weaknesses, opportunities and challenges presented to them by the new decentralized modality of fi sheries governance at the local level.

In addition, the relationship between local councils and local actors—like harbour masters and master fishermen (and their associated roles and responsibilities) — is ill-defined by the present legislation. To date, the Freetown City Council is the only coastal council that has permitted harbour masters to retain 20 per cent of the revenues collected—not just to maximize licence registrations, but also as a means to compensate them for the wide-ranging activities they undertake on behalf of the community. (These include taking care of the harbour in terms of sanitation, and conducting rescue missions, to name but two.) Concern has also been expressed about institutional responsibilities following government endorsement of the LGA2004. Local fishers have been unable to access justice and have nowhere to channel their concerns — when, for example, their gears were destroyed by trawlers — as the responsibilities of the councils and the MFMR have not yet been properly demarcated. Moreover, producers’ organizations such as the Sierra Leone Artisanal Fishermen’s Union (SLAFU) and the Sierra Leone Amalgamated Artisanal Fishermen’s Union (SLAAFU) are weak, perhaps because they are undemocratic and maintain an uneasy relationship between themselves. SLAFU represents local fishermen and those in ancillary occupations (such as boat builders, wood cutters, fish processors, basket makers, machinists, transporters, and so on). Formed on 26 December 2001, it aims to harmonize the concerns of members and act as their collective vanguard. SLAFU develops bye-laws for the sustainable use of resources while campaigning against ecosystem misuse such as fishing with illegal gear and on nursery grounds. Other objectives include improving landing site sanitation and management, prevention of pollution and mangrove deforestation, ensuring safety of fishermen at sea, and resolution of conflicts. The organization was formed by prominent fishers in the Tombo fishing community in the Western Area, who make up the executive.

Umbrella organization

Efforts to develop SLAFU into a national organization have been met with resistance from fishers in other areas of the country who see SLAFU as undemocratic (because members did not have a say in choosing those who represent them) and biased in favour of the Western Area where it was formed. SLAAFU, on the other hand, as its name implies, seeks to act as an umbrella organization but has met with resistance from SLAFU; the relationship between the two organizations can best be described as suspicious. The development of an acceptable and democratic producers’ organization remains an important concern in the artisanal fisheries of Sierra Leone.

As a consequence of the LGA2004, the artisanal fisheries sector of Sierra Leone offers favourable opportunities for development by:

-

bringing the decision-making processes closer to resource users, local actors and interested stakeholders;

-

assuring transparency and accountability, since all stakeholders are involved;

-

building capacity (in terms of fisheries resource management) at the community level;

-

producing management plans with the full participation of local actors;

-

identifying needs, including unmet needs, at the local level;

-

promoting local or community resource management responsibility;

-

ensuring that an enabling framework for sustainable fisheries development and co-management will be created and enhanced over time; and

-

incorporating resource user groups like SLAFU, as roles and responsibilities get better defined.

There are also clear challenges facing the sector. These include:

-

the virtual absence of State structures, and low human resource capacity in local administration systems;

-

the inadequacy of the devolved artisanal fisheries function to ensure effective fisheries management at the local level;

-

the failure to fully identify roles and responsibilities of all stakeholders;

-

limited funds (funds are allocated on a quarterly basis to local councils so as to implement the devolved functions);

-

conflicts between/among different resource users and parties like SLAFU, SLAAFU, local councils, fishers and fishmongers;

-

ensuring the legitimate election of key local actors like harbour masters and master fishermen; and limiting central government political influence or intervention.

Key words

fishermen’s organization, fishing, traditional fishing, fisherman

, Sierra Leone

file

Notes

This article was originally published in Samudra 55, March 2010. It is also available in French and Spanish.

Source

Sierra Leone Fisheries: www.illegal-fishing.info/sub_approach.php?country_title=sierra+leone

Sierra Leone Fisheries Profile: www.imcsnet.org/imcs/docs/sierra_leone_fishery_profile_apr_08.pdf

FAO Country Profile – Sierra Leone: www.fao.org/fishery/countrysector/FI-CP_SL/en

ICSF (International Collective in Support of Fishworkers) - 27 College Road, Chennai 600006, INDIA - Tel. (91) 44-2827 5303 - Fax (91) 44-2825 4457 - India - www.icsf.net - icsf (@) icsf.net